Uncategorized

Tula, Russia: Land of Gingerbread, Samovars and Tolstoy

Fall was always my favorite season growing up.

Something about the air turning crisper, the weather getting colder. The leaves turning yellow and brown and orange. And of course Halloween.

It’s that back-to-school weather that any person growing up in the United States loves.

So it was a special treat to be able to experience what fall was like in a different country on a different continent, in a country so unknown in the west. To experience fall in Russia.

Maybe it’s because the season is so short here, but autumn in Russia is truly special.

For starters, it only lasts one month. Fall rolls in during the second half of September and ends in the first half of October. After that winter is already in the air.

But during that brief four-week period, when the country transitions from summer to winter, the Russian countryside explodes into the most beautiful mosaic of red and orange and brown and yellow.

They call it ‘zolotaja osenj’ here, or ‘golden fall.’

It was during this time of year I decided to head outside of Moscow and visit Tula, a city located three hours south of Moscow.

The year was 2017. I was living in Moscow working for a Russian newspaper. October had just arrived.

I was living with another American at the time working in Moscow. We both didn’t want to waste a beautiful crisp sunny autumn day cooped up in Moscow in the apartment.

So we took out a map and looked at what cities nearby we could visit.

We looked North, East, West and finally South. And there she was. Tula.

We’d read a lot of good things about Tula before. How Tula was the birthplace of Leo Tolstoy. That it was where a traditional Russian desert called pryaniki, or ‘gingerbread’ originated.

How for centuries Tula supplied the Russian empire with weapons and arms. And that samovars, what Russians used to make tea and keep water hot, originated from there.

Throw in a Kremlin too, which the city had, and the choice was obvious. We should visit Tula.

And off we went. To enjoy the Russian autumn in the Russian provinces.

How to get to Tula

There are two ways to get to Tula from Moscow. You can take a suburban train, known as elektrichkas, or you can take a regular train. The regular train costs more, and will take you there directly. In this case, Tula is usually the first stop of a longer train ride headed south toward Voronezh and Ukraine.

The other option, which we opted for, was the elektrichka. Elektrichkas are suburban trains that connect surrounding cities to Moscow. The elektrichka takes longer, three hours as opposed to an hour and a half. But the benefit is it is cheap. And you get to see all the smaller cities the train stops in.

When we went, the train was packed full of Russians heading to their dachas for the weekend.

Three hours later and we found ourselves hopping off the train at Tula’s main train station.

Three hours later and we found ourselves hopping off the train at Tula’s main train station.

There were a few military vehicles on display nearby. Tula was traditionally a major arms manufacturer in the Russian Empire, fueled by the Tula Arms Plant founded by Peter The Great in 1712.

There were a few military vehicles on display nearby. Tula was traditionally a major arms manufacturer in the Russian Empire, fueled by the Tula Arms Plant founded by Peter The Great in 1712.

But what Tula is really famous for is Russian gingerbread, a traditional Russian desert known as Pryaniki.

But what Tula is really famous for is Russian gingerbread, a traditional Russian desert known as Pryaniki.

It comes with jam, honey or sweetened condensed milk inside, while the outside has cool drawings depicting traditional aspects of Russian culture. They were selling these right outside the train station and all over the city.

It comes with jam, honey or sweetened condensed milk inside, while the outside has cool drawings depicting traditional aspects of Russian culture. They were selling these right outside the train station and all over the city.

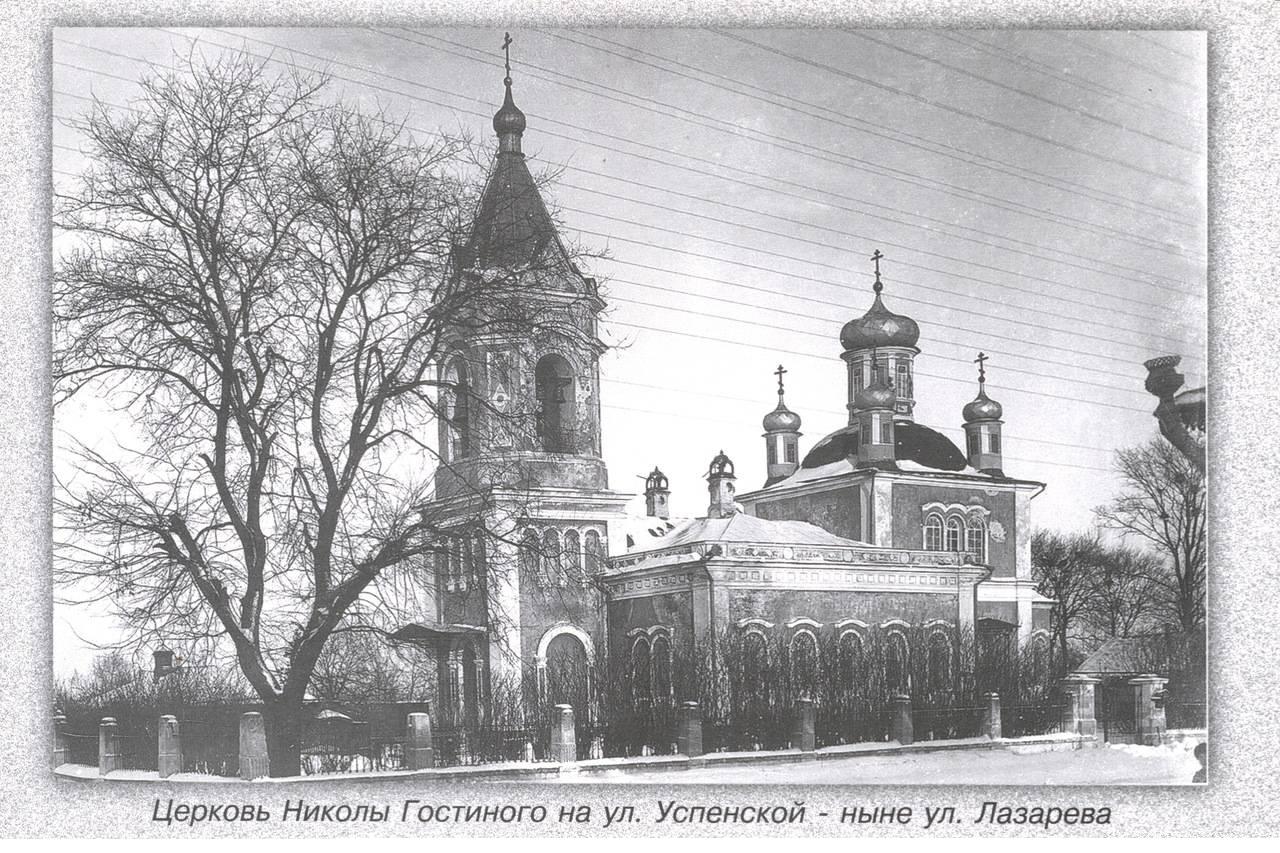

When we got to the center we saw a huge black and white photo of what Tula looked like before the communists took power in 1917.

When we got to the center we saw a huge black and white photo of what Tula looked like before the communists took power in 1917.

As you can see the center was dominated by a Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Like most Russian cities, Tula suffered a tragic fate after the Bolshevik revolution. The church in the photo above was located in the central square of the city and stood as a historical symbol of the town for generations. It was torn down in the 1920s, just like the majority of the surrounding buildings in the photo. Stalin wanted to implemented his vision of a communist future at all costs, and any symbols of the previous Czarist order were to be erased.

As you can see the center was dominated by a Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Like most Russian cities, Tula suffered a tragic fate after the Bolshevik revolution. The church in the photo above was located in the central square of the city and stood as a historical symbol of the town for generations. It was torn down in the 1920s, just like the majority of the surrounding buildings in the photo. Stalin wanted to implemented his vision of a communist future at all costs, and any symbols of the previous Czarist order were to be erased.

Churches all across the Soviet Union were declared to have ‘no historic value’ and torn down. Churches that were several centuries old. Comunist style administration buildings were put in their place. Monuments to Russian czars were also destroyed and replaced by statues of Lenin.

Tula didn’t escape this fate. Here is Tula’s central square in 2017. All of those old buildings in the black and white photo above showing Tula before the revolution are gone.

The enormous grey building behind Lenin is where Tula’s church used to stand. Today it is the administrative building of Tula and the Tula Oblast.

The enormous grey building behind Lenin is where Tula’s church used to stand. Today it is the administrative building of Tula and the Tula Oblast.

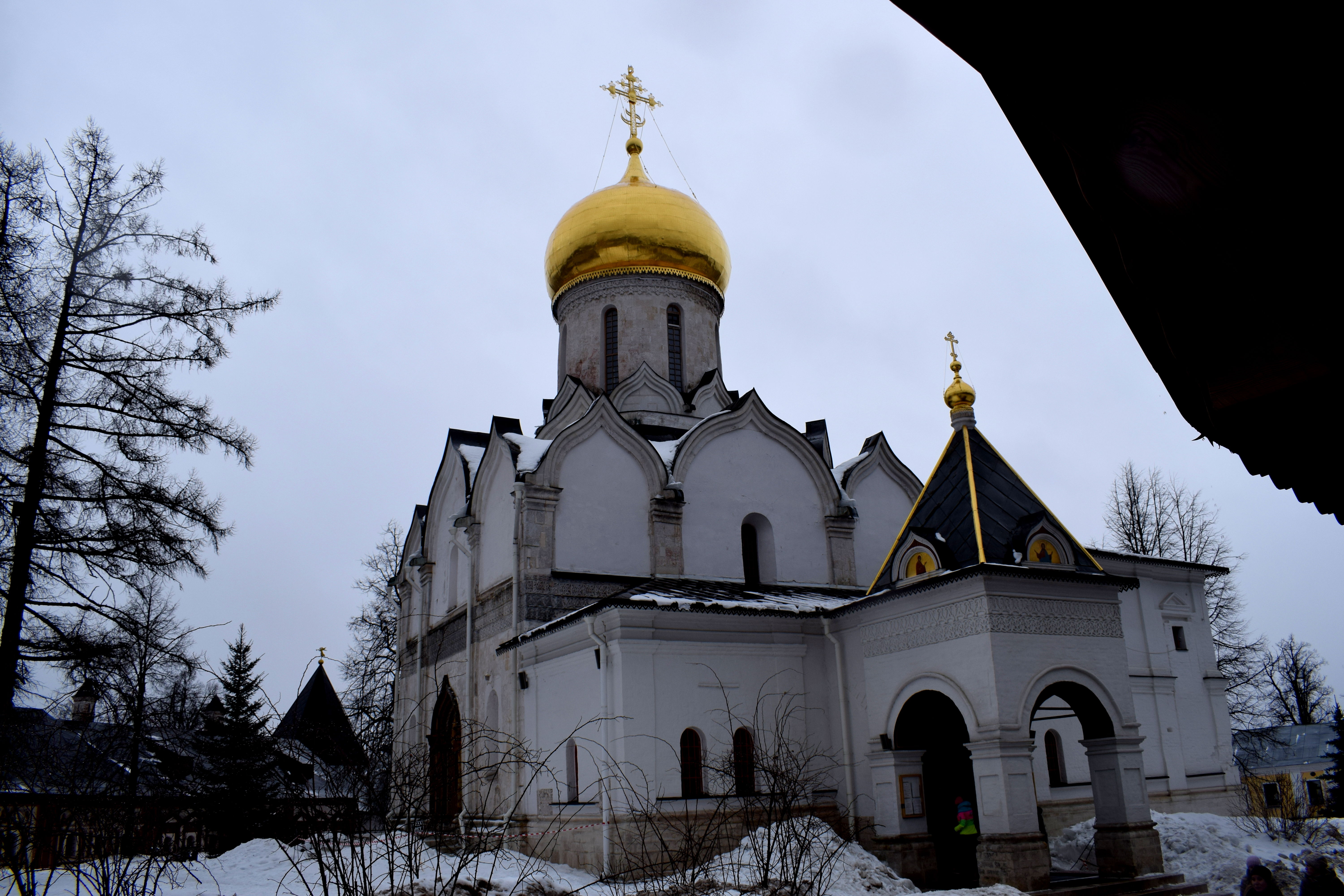

Of course, not all of Tula was destroyed during the Soviet period. Nearby the statue to Lenin is the Uspensky Sobor, one of the few churches that survived the destruction of the 1920s.

Of course, not all of Tula was destroyed during the Soviet period. Nearby the statue to Lenin is the Uspensky Sobor, one of the few churches that survived the destruction of the 1920s.

The Uspensky Sobor was built between 1898-1902. The Soviet authorities actually tried to blow up the church in the 1930s, but miraculously the church withstood the blast. A decision was then taken to empty it of all its religious artifacts and close it down. The domes were removed and the building was used as storage for the city’s archives.

The Uspensky Sobor was built between 1898-1902. The Soviet authorities actually tried to blow up the church in the 1930s, but miraculously the church withstood the blast. A decision was then taken to empty it of all its religious artifacts and close it down. The domes were removed and the building was used as storage for the city’s archives.

In the 1980s under Gorbachev an effort was made to restore churches that had been neglected for decades under communism. The domes were put back in place and religious services began once more.

In 2006 the building was finally returned back to the Russian Orthodox Church. Somehow, Tula’s Uspensky Sobor managed to survive 80 years of neglect under Soviet rule. Let’s hope the 21st century treats it better.

Next to the Uspensky Sobor is Tula’s Preobrazhensky church. Built in 1842 in the Russian classical style, it is another building from the first half of the 19th century that still stands in the city.

Next to the Uspensky Sobor is Tula’s Preobrazhensky church. Built in 1842 in the Russian classical style, it is another building from the first half of the 19th century that still stands in the city.

It too faced threats of disappearing forever under the communists. In the 1920s the dome was torn down but the remainder of the building was left untouched. For a while it functioned as a school, and then in 1960 the building was deemed to be part of the city’s architectural heritage and received protected status.

But of course, Tula’s main attraction is its Kremlin. Behind that nice building in purple from the 19th century is the city’s Kremlin, the heart of the city.

But of course, Tula’s main attraction is its Kremlin. Behind that nice building in purple from the 19th century is the city’s Kremlin, the heart of the city.

Kremlin means ‘fortress’ in Russian. And you can find Kremlins all over Russia in the country’s historic cities. In fact, the best way to know what cities to visit in Russia is to check whether they have a Kremlin. If there is a Kremlin, that means the city has existed for centuries and is worth visiting.

Kremlin means ‘fortress’ in Russian. And you can find Kremlins all over Russia in the country’s historic cities. In fact, the best way to know what cities to visit in Russia is to check whether they have a Kremlin. If there is a Kremlin, that means the city has existed for centuries and is worth visiting.

Tula’s Kremlin was built in 1514-1520 by the order of Vasili III of Russia. Vasili III was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505-1533. In 1507 he gave the order to construct the Kremlin on the Upa River to protect the city from ongoing raids from the east.

Tula’s Kremlin was built in 1514-1520 by the order of Vasili III of Russia. Vasili III was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505-1533. In 1507 he gave the order to construct the Kremlin on the Upa River to protect the city from ongoing raids from the east.

It’s interesting to compare Kremlins in Russia and when they were built. As far as Tula is concerned, it’s Kremlin isn’t the oldest, but neither is it the youngest.

- Veliky Novgorod – 1490

- Moscow – 1495

- Nizhny Novgorod – 1515

- Tula – 1520

- Zaraisk – 1531

- Kolomna – 1531

- Astrakhan – 1581

- Smolensk – 1602

- Rostov – 1680

There’s actually a lot more kremlins in Russia, depending on how you define a Kremlin. Technically many monetarists could be considered Kremlins, but are classified as religious objects, such as Sergiev Posad or Zvenigorod. Some have only been partly preserved, such as Kolomna. In any case, Tula gets the honor of being one of a handful of Russian cities with a Kremlin that’s been fully preserved.

I was surprised at how clean it was inside of Tula’s Kremlin. It was a beautiful place to walk around and relax in. We went in the fall when it was cold outside so there were few people around, but in the summer the inside of the Kremlin fills up with people and even holds concerts inside.

I was surprised at how clean it was inside of Tula’s Kremlin. It was a beautiful place to walk around and relax in. We went in the fall when it was cold outside so there were few people around, but in the summer the inside of the Kremlin fills up with people and even holds concerts inside.

Within the Kremlin there are a few historic buildings.

Within the Kremlin there are a few historic buildings.

The towers are beautifully preserved. These arches served as lookout posts to shoot at invading armies from the south and east in the 16th century. The Kremlin protected the city’s religious and political elite.

The towers are beautifully preserved. These arches served as lookout posts to shoot at invading armies from the south and east in the 16th century. The Kremlin protected the city’s religious and political elite.

There are two cathedrals located within Tula’s Kremlin. The Assumption Cathedral (1762-1766) and the Epiphany Cathedral (1855-1863).

There are two cathedrals located within Tula’s Kremlin. The Assumption Cathedral (1762-1766) and the Epiphany Cathedral (1855-1863).

The grass and walls of the Kremlin were impeccably clean. What I loved about the Kremlin in Tula was that it was open to the public. Anyone could walk inside and enjoy the city’s main historical landmark. The same is true of the Kremlins in Nizhny Novgorod and Veliky Novgorod.

The grass and walls of the Kremlin were impeccably clean. What I loved about the Kremlin in Tula was that it was open to the public. Anyone could walk inside and enjoy the city’s main historical landmark. The same is true of the Kremlins in Nizhny Novgorod and Veliky Novgorod.

In Moscow, the Kremlin is closed to the public. In order to visit, you have to pay. And as a result, nobody gets to enjoy the Kremlin. Tourists will pay and go inside when they visit the city. But the actual residents of Moscow, the people that live in the city, never get to enjoy it. It feels separated from the city, not like an integral part of it.

It wasn’t always like this. Up until the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, Moscow’s Kremlin was open to the public and anybody could walk in and out of it. It functioned just like the Kremlins in Tula, Nizhny Novgorod, Veliky Novgorod and so forth.

Moscow should learn from these cities and open their own Kremlin up to the public. The city would become much more attractive.

Outside of the Kremlin looking at one of the Kremlin’s towers and observation posts.

Outside of the Kremlin looking at one of the Kremlin’s towers and observation posts.

Of course, there is more to Tula than just the Kremlin. Despite significant damage the city faced in WWII and attempts by the Soviets to raze down historical buildings, a number of streets in the city were filled with architecture from the 19th and early 20th century.

Of course, there is more to Tula than just the Kremlin. Despite significant damage the city faced in WWII and attempts by the Soviets to raze down historical buildings, a number of streets in the city were filled with architecture from the 19th and early 20th century.

It’s buildings like these that make it especially enjoyable for me to visit smaller Russian cities. They are a testament to the fundamentally European nature of Russia. There really is nothing distinguishing these kind of buildings from any others you find in Europe.

It’s buildings like these that make it especially enjoyable for me to visit smaller Russian cities. They are a testament to the fundamentally European nature of Russia. There really is nothing distinguishing these kind of buildings from any others you find in Europe.

The only difference is that they were in slightly worse shape in Tula. One problem I noticed in the city was the huge amount of advertisements that covered up many buildings. The city clearly needed a design code, so that store signs and advertisements would not cover up the facades of buildings. Tula could learn from other cities in Eastern Europe like Szeged, Hungary that have successfully managed to implement a design code.

The only difference is that they were in slightly worse shape in Tula. One problem I noticed in the city was the huge amount of advertisements that covered up many buildings. The city clearly needed a design code, so that store signs and advertisements would not cover up the facades of buildings. Tula could learn from other cities in Eastern Europe like Szeged, Hungary that have successfully managed to implement a design code.

Despite the advertising, the historic nature of Tula’s center shined through. You could tell this was a city that had stood here for a long time, with history to it.

Despite the advertising, the historic nature of Tula’s center shined through. You could tell this was a city that had stood here for a long time, with history to it.

Without the old buildings, Tula would lose its character. It’s these kind of buildings that need to be preserved at all costs. All over Russia, unfortunately, provincial cities are seeing their historical centers torn down. There are a lot of reasons for this – corruption, poor laws, education – but the net result is that these towns lose any tourist potential they still have. Let’s hope that Tula does not follow the same path and preserves the architectural heritage it has left.

Without the old buildings, Tula would lose its character. It’s these kind of buildings that need to be preserved at all costs. All over Russia, unfortunately, provincial cities are seeing their historical centers torn down. There are a lot of reasons for this – corruption, poor laws, education – but the net result is that these towns lose any tourist potential they still have. Let’s hope that Tula does not follow the same path and preserves the architectural heritage it has left.

As things stand right now, the city is in a great position to set itself up as a major tourist attraction for foreigners who visit Moscow and want to do a day trip to a city nearby.

As things stand right now, the city is in a great position to set itself up as a major tourist attraction for foreigners who visit Moscow and want to do a day trip to a city nearby.

There is already talk of Russia lifting tourist restrictions for Europeans in 2021. After that, any EU citizen will be able to come to Russia without going through the complicated process of obtaining a visa. When this takes place, tourism to Russian cities will skyrocket. By preserving these buildings, Tula will ensure that foreigners will actually have something to see when they visit.

There is already talk of Russia lifting tourist restrictions for Europeans in 2021. After that, any EU citizen will be able to come to Russia without going through the complicated process of obtaining a visa. When this takes place, tourism to Russian cities will skyrocket. By preserving these buildings, Tula will ensure that foreigners will actually have something to see when they visit.

One of Tula’s main streets downtown.

One of Tula’s main streets downtown.

A half-finished balcony.

A half-finished balcony.

A smaller side street in Tula. If these buildings were renovated properly, they could form great places for small cafes, bookshops, coworking spaces and so forth.

A smaller side street in Tula. If these buildings were renovated properly, they could form great places for small cafes, bookshops, coworking spaces and so forth.

A lot of areas in the city had an abandoned feeling to them. The historic gates here used to open up to a cafe. It was empty and overgrown with trees now.

A lot of areas in the city had an abandoned feeling to them. The historic gates here used to open up to a cafe. It was empty and overgrown with trees now.

A look down toward the center of Tula. The tall church in the background is where Tula’s Kremlin is located.

A look down toward the center of Tula. The tall church in the background is where Tula’s Kremlin is located.

One problem in Tula were the wide streets that favored cars. Tula’s main street in the city that went through the center of the city had three lanes for cars going in each direction.

It was no wonder, therefore that cars drove very fast. In fact, I was quite surprised at just how loud Tula was for a city of only half a million people. It felt like on every street there was the constant noise of cars rushing by.

What should Tula do instead? Streets like these should be reduced in size and preference given to pedestrians and cyclists. Two lanes in the middle should go toward a tram line, the other two narrowed in size to make way for a bike lane going in both directions.

Tula in fact, had tram lines operating on its main streets up until WWII, before the government decided to get rid of them.

Giving the streets back to the people would make the city a more comfortable place to live.

Another beautiful building from the 19th century. It was early October and many trees had already lost most of their leaves.

Another beautiful building from the 19th century. It was early October and many trees had already lost most of their leaves.

I love Tula.

I love Tula.

What a beauty.

What a beauty.

These kind of buildings are a testament to Tula’s European past.

These kind of buildings are a testament to Tula’s European past.

No different from any others you can find in Europe. At the top of the building it says: “I obey the law, I obey the people.”

No different from any others you can find in Europe. At the top of the building it says: “I obey the law, I obey the people.”

However, there is one form of architecture completely unique to Russia that you won’t find in Europe. And those are traditional Russian wooden buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, there is one form of architecture completely unique to Russia that you won’t find in Europe. And those are traditional Russian wooden buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

When I first came to Russia, these kind of wooden buildings completely surprised me. I had never seen anything like them in any countries I had visited before in my life. I loved them.

When I first came to Russia, these kind of wooden buildings completely surprised me. I had never seen anything like them in any countries I had visited before in my life. I loved them.

They were completely unique to Russia. We don’t have these kind of buildings in Serbia or in the Balkans. I’ve never seen them in other countries in Eastern Europe I’ve been to, like Hungary or Slovakia.

They were completely unique to Russia. We don’t have these kind of buildings in Serbia or in the Balkans. I’ve never seen them in other countries in Eastern Europe I’ve been to, like Hungary or Slovakia.

The majority of Russians actually lived precisely in these kinds of wooden homes before the revolution in 1917. Many people continue to live in them to this today.

The majority of Russians actually lived precisely in these kinds of wooden homes before the revolution in 1917. Many people continue to live in them to this today.

Unfortunately this kind of architecture is disappearing at alarming rates all cross Russia. The homes fall into disrepair because young people move away from cities. Developers offer to buy the homes from poor residents. Instead of reconstructing them, they tear them down and build modern apartments.

Unfortunately this kind of architecture is disappearing at alarming rates all cross Russia. The homes fall into disrepair because young people move away from cities. Developers offer to buy the homes from poor residents. Instead of reconstructing them, they tear them down and build modern apartments.

It doesn’t help that cities rarely afford these kind of homes historical status. More often than not, they sit abandoned in cities as eyesores until they collapse.

It doesn’t help that cities rarely afford these kind of homes historical status. More often than not, they sit abandoned in cities as eyesores until they collapse.

Other times they are put up for sale my view, Russia should take all possible measures to

Other times they are put up for sale my view, Russia should take all possible measures to

This one was up for sale.

This one was up for sale.

Here was one that was in a terrible state, even though you could tell that not long ago it was a beautiful building. I took this picture in 2017, when it still could have been renovated.

Here was one that was in a terrible state, even though you could tell that not long ago it was a beautiful building. I took this picture in 2017, when it still could have been renovated.

But I took a look at Google Maps in 2020 and it was gone. Whoever decided to buy the property figured it was too expensive to renovate the existing building. Instead they tore it down completely and a piece of Tula’s history is lost forever.

But I took a look at Google Maps in 2020 and it was gone. Whoever decided to buy the property figured it was too expensive to renovate the existing building. Instead they tore it down completely and a piece of Tula’s history is lost forever.

If nothing is done to intervene, this is going to be the fate of every building on this street. Here’s another one in bad shape. Nothing stops someone from buying this property and tearing it down to build a new modern building in its place.

If nothing is done to intervene, this is going to be the fate of every building on this street. Here’s another one in bad shape. Nothing stops someone from buying this property and tearing it down to build a new modern building in its place.

The beauty of these buildings is that they preserve what Tula looked like 100 years ago. You could be in Tula in 1905 and this street would have looked exactly the same.

The beauty of these buildings is that they preserve what Tula looked like 100 years ago. You could be in Tula in 1905 and this street would have looked exactly the same.

A look down Pirogova Street.

A look down Pirogova Street.

Given proper care, these buildings could be converted into hostels or mini hotels, cafes, bookshops, souvenir shops, coworking spaces. There’s tons of businesses that work better using traditional architecture and you don’t need a modern equivalent.

Given proper care, these buildings could be converted into hostels or mini hotels, cafes, bookshops, souvenir shops, coworking spaces. There’s tons of businesses that work better using traditional architecture and you don’t need a modern equivalent.

What I love most about these buildings is how colorful they are. They are all painted in different colors.

Unfortunately many of them were in bad shape. Traditional wooden buildings in Russia are in danger of disappearing forever. All across the country these buildings are being torn down as people move to cities and forget about the buildings where their grandparents grew up and came from. I wrote an entire separate post about the topic here about a street in Tula that was filled with these wooden buildings.

Tula is mostly a flat city, but there is a slight hill at the top of which the Всехсвятский кафедральный собор (Vsehsvyatski kafederalni sobor) is located.

Tula is mostly a flat city, but there is a slight hill at the top of which the Всехсвятский кафедральный собор (Vsehsvyatski kafederalni sobor) is located.

This is one of the oldest cemeteries in the city. Built in 1772, it contained some of the oldest graveyards and tombs in the city from over 100 years ago.

A few notes about Russian graveyards. As a rule cemeteries in Russia are located in the woods. This is something I find unique specifically to Russia, and is not the case in Serbia or the Balkans where my family is from and is definitely different from the United States.

A few notes about Russian graveyards. As a rule cemeteries in Russia are located in the woods. This is something I find unique specifically to Russia, and is not the case in Serbia or the Balkans where my family is from and is definitely different from the United States.

An old building in the cemetery.

An old building in the cemetery.

The cemetery had a distinctly creepy feeling in the October weather. It was a perfect fall day. But the cemetery felt abandoned with many of the graveyards falling apart. You can read a separate post on the topic here.

The cemetery had a distinctly creepy feeling in the October weather. It was a perfect fall day. But the cemetery felt abandoned with many of the graveyards falling apart. You can read a separate post on the topic here.

The church and the graveyard at the top of the hill in the distance. This was probably my favorite street in Tula.

The church and the graveyard at the top of the hill in the distance. This was probably my favorite street in Tula.

Another old building.

Another old building.

One reason we chose to visit Tula was because the city hosts the brewery to a relatively famous Russian beer called Salden’s. Although we didn’t have time to visit the brewery, we decide to try some in the city in a small store selling it.

One reason we chose to visit Tula was because the city hosts the brewery to a relatively famous Russian beer called Salden’s. Although we didn’t have time to visit the brewery, we decide to try some in the city in a small store selling it.

Back near the Kremlin. The fall weather was just perfect. It was a crisp, cold October day, with Halloween just around the corner, and the Kremlin looked amazing with the leaves turning brown and falling to the ground.

Back near the Kremlin. The fall weather was just perfect. It was a crisp, cold October day, with Halloween just around the corner, and the Kremlin looked amazing with the leaves turning brown and falling to the ground.

A statue dedicated to the Tulski Pryanik, or Tula Gingerbread, a desert that has existed since 1685. The Uspensky Sobor is in the distance.

A statue dedicated to the Tulski Pryanik, or Tula Gingerbread, a desert that has existed since 1685. The Uspensky Sobor is in the distance.

Fall in Russia is my favorite season. Unfortunately it is really short. It lasts for just one month, typically from the second half of September to the first half of October. After that the weather gets significantly colder.

Fall in Russia is my favorite season. Unfortunately it is really short. It lasts for just one month, typically from the second half of September to the first half of October. After that the weather gets significantly colder.

In these photos you can see the Russian autumn in all its beauty.

In these photos you can see the Russian autumn in all its beauty.

Incredible.

Incredible.

Tula’s Kremlin is one of my favorites in Russia. One reason is that it is actually open to the public, unlike the Moscow Kremlin. Moscow should learn from Tula and open up theirs to the public as well instead of charging people 700 rubles to go inside. Before the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, the Moscow Kremlin was open to the public and anyone could visit it.

Tula’s Kremlin is one of my favorites in Russia. One reason is that it is actually open to the public, unlike the Moscow Kremlin. Moscow should learn from Tula and open up theirs to the public as well instead of charging people 700 rubles to go inside. Before the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, the Moscow Kremlin was open to the public and anyone could visit it.

The back entrance to the Kremlin.

The back entrance to the Kremlin.

A monument to the fallen soldiers in WWII.

A monument to the fallen soldiers in WWII.

There was an eternal flame at this monument, just like most Soviet monuments dedicated to WWII.

There was an eternal flame at this monument, just like most Soviet monuments dedicated to WWII.

Fall in Tula is so picturesque with the Kremlin in the background.

Fall in Tula is so picturesque with the Kremlin in the background.

Kids playing.

Kids playing.

Looking back out at the city.

Looking back out at the city.

A final look at Tula’s administrative building before the sun set. This was definitely the ugliest building in the city. In my opinion, they should do bring back the church that used to stand there.

A final look at Tula’s administrative building before the sun set. This was definitely the ugliest building in the city. In my opinion, they should do bring back the church that used to stand there.

We finished the day by visiting Tula’s Samovar museum. It was a modest little exhibition that displayed some of the oldest samovar’s that were once made in the city.

We finished the day by visiting Tula’s Samovar museum. It was a modest little exhibition that displayed some of the oldest samovar’s that were once made in the city.

Samovars were used by Russians in czarist times to keep water hot for tea and soup. A flame in the bottom of the Samovar would be lit that would warm up the water in the container. The handle could then be turned so that the hot water pours out.

Samovars were used by Russians in czarist times to keep water hot for tea and soup. A flame in the bottom of the Samovar would be lit that would warm up the water in the container. The handle could then be turned so that the hot water pours out.

Tula was the city where the majority of Russian samovars were produced in the 19th century. You could find them all over Europe and chance are if you live in an old house and look in the attic, you will find a samovar that was made in the city of Tula.

Conclusion

Tula was an amazing city to visit in the fall. Russia can have extreme weather. Most of the year is covered in snow, but you have brief glimpses of fall, spring and summer that can be enjoyed.

These photos capture what fall in Russia is like. We happened to spend them in Tula, but really, any Russian city will look this beautiful in the fall.

When it comes t othe city of Tula itself, it is a great day trip outside of Moscow. The city is beaming with history. The armaments factory, the Kremlin, the wooden buildings in the center of the city, the beautiful cemetery atop the hill and the delicious Russian pryaniki all combine to make this worth the trek outside of Moscow.

Be sure to add it to your itinerary when you visit Russia and Moscow.

Moscow Region Day Trips: Sergiev Posad

Sergiev Posad is the next destination on our tour exploring historical towns around Moscow you can visit in a day.

Sergiev Posad is one of Russia’s oldest cities founded in the 14th century. It is also a Golden Ring city in Russia, which are a series of towns northeast of Moscow which form the ancient core of medieval Russia and which have seen a lot of their historic architecture preserved to this day.

You would think that the further west you go in Russia toward Europe, the more European the towns get, but that isn’t quite the case. In fact, because Russia suffered numerous invasions from Europe over the course of the centuries, beginning with the Poles and Swedes, the French in the 19th century and the Germans in the 20th century, most of the cities that lie west of Moscow suffered repeated destruction.

In contrast, towns east of Moscow have largely been preserved. The last true invader to attack Russia from the east were the Mongolians under Genghis Khan. Since then, these cities have remained untouched and miraculously survived Soviet attempts to wipe out religion in Russia in the 1930’s.

Sergiev Posad is one of those cities.

The easiest way to get to Sergiev Posad is to take a train from Moscow’s Yaroslavsky Station. Trains leave every 10-20 minutes. The ride costs 176 rubles in one direction, or about $3. The city is located 67 kilometers away and it takes 1.5 hours to get there.

I always like to judge cities based on how easily accessible their centers are from the train station. Sergiev Posad’s train station had a decent location. The city center was only a 15 minute walk away and there were some historical buildings on the way.

I always like to judge cities based on how easily accessible their centers are from the train station. Sergiev Posad’s train station had a decent location. The city center was only a 15 minute walk away and there were some historical buildings on the way.

Of course like a lot of Russian cities, the city decided to locate its bus station right next to its train station. So despite having nice buildings, they were ruined by the ‘marshutkas’, or shuttle buses, that dominate smaller Russian cities. Sooner or later, Russian cities should get rid of these marshutkas and invest in proper buses or trams.

Of course like a lot of Russian cities, the city decided to locate its bus station right next to its train station. So despite having nice buildings, they were ruined by the ‘marshutkas’, or shuttle buses, that dominate smaller Russian cities. Sooner or later, Russian cities should get rid of these marshutkas and invest in proper buses or trams.

Walking toward Sergiev Posad’s city center.

Walking toward Sergiev Posad’s city center.

March is a wildcard month in Russia in terms of weather. Whereas in most other countries March signifies the start of spring, in Russia March is completely inconsistent. Often you will get a week of warm spring weather followed by a week of cold brutal winter and then back to spring. This kind of see-sawing usually continues for all of April and even in May.

March is a wildcard month in Russia in terms of weather. Whereas in most other countries March signifies the start of spring, in Russia March is completely inconsistent. Often you will get a week of warm spring weather followed by a week of cold brutal winter and then back to spring. This kind of see-sawing usually continues for all of April and even in May.

A panoramic view approaching Sergiev Posad. The city is most famous for the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius Monastery, one of the oldest and biggest monasteries in all of Russia, founded in 1337 by St. Sergei of Radonezh.

A panoramic view approaching Sergiev Posad. The city is most famous for the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius Monastery, one of the oldest and biggest monasteries in all of Russia, founded in 1337 by St. Sergei of Radonezh.

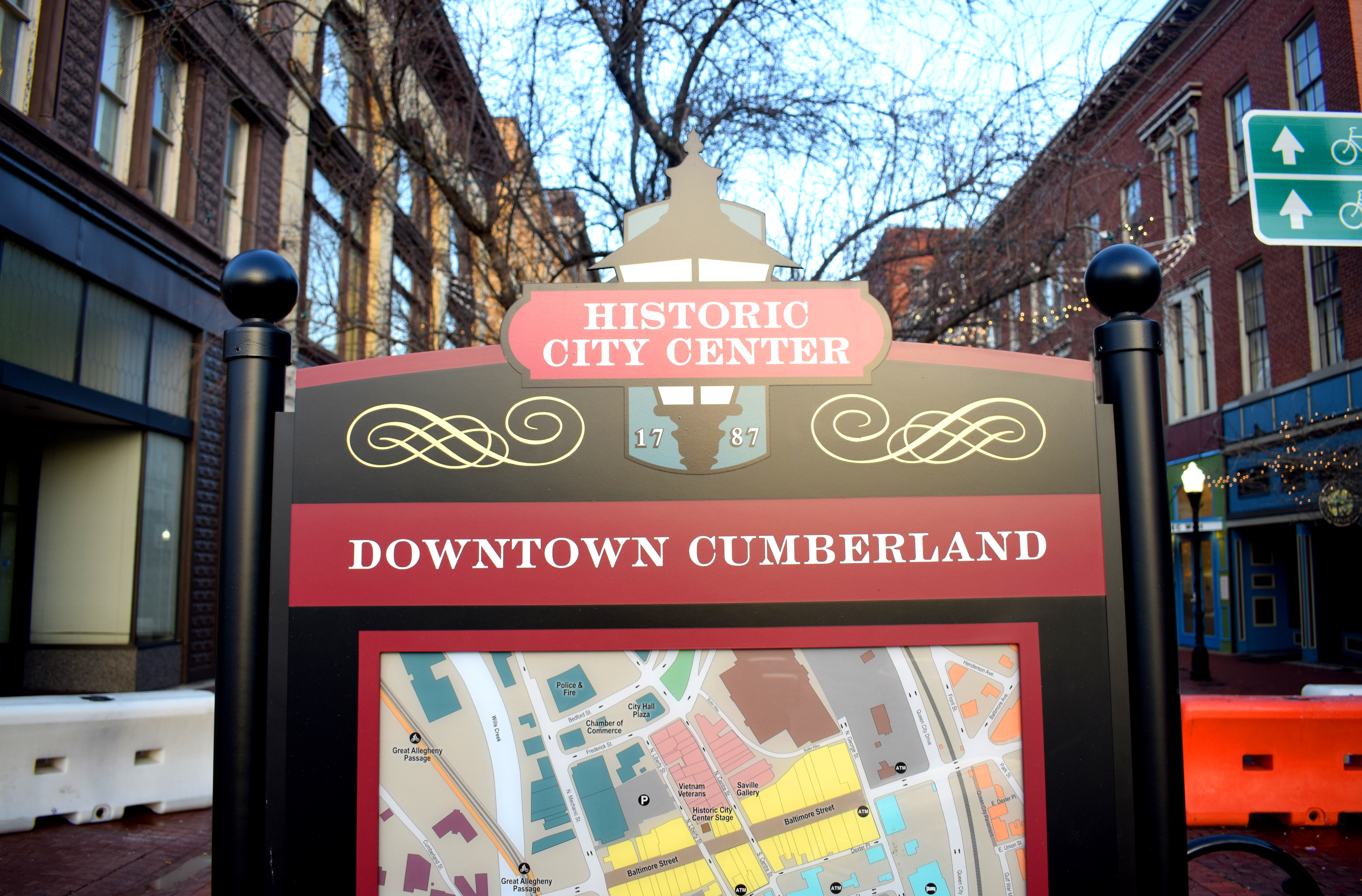

Near the entrance to the town is a monument celebrating the 700th anniversary of Sergiev Posad. The city got its name Sergiev Posad only in 1782 following a decree by Russian Empress Catherin II to name the city after the man who founded the monastery, St. Sergei of Radonezh. From 1930 to 1991 the city was renamed to Zagorsk after a famous communist leader. The city reverted back to its old name after the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991.

Near the entrance to the town is a monument celebrating the 700th anniversary of Sergiev Posad. The city got its name Sergiev Posad only in 1782 following a decree by Russian Empress Catherin II to name the city after the man who founded the monastery, St. Sergei of Radonezh. From 1930 to 1991 the city was renamed to Zagorsk after a famous communist leader. The city reverted back to its old name after the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991.

The best time to visit Sergiev Posad is in the summer. There are a number of lakes and small ponds sprinkled throughout the city around the monastery which were frozen over in March.

The best time to visit Sergiev Posad is in the summer. There are a number of lakes and small ponds sprinkled throughout the city around the monastery which were frozen over in March.

The Pyatnitsky Well Chapel, one of the early churches in the city built in the 1600’s.

The Pyatnitsky Well Chapel, one of the early churches in the city built in the 1600’s.

An other side of the street on the opposite side of the chapel is the Vvedenskaya Church, built in 1547. In was reconstructed in 1621 and again in 1740. In 1928 the Bolsheviks closed it down and it did not reopen as a church until after 1991.

An other side of the street on the opposite side of the chapel is the Vvedenskaya Church, built in 1547. In was reconstructed in 1621 and again in 1740. In 1928 the Bolsheviks closed it down and it did not reopen as a church until after 1991.

The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, Sergiev Posad’s main tourist attraction. One of the towers was being reconstructed when we visited.

The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, Sergiev Posad’s main tourist attraction. One of the towers was being reconstructed when we visited.

St. Sergius who founded the monastery was one of the most respected religious leaders in Russia during his time. He had over 4oo followers in Russia who would go on to found many other monasteries in northeastern Russia in the 14th century, including the Solovetsky, Kirillov and Simonov monasteries. St. Sergius was also an avid supporter of Dmitry Donskoi in his struggle with the Tatars, sending his monks to fight alongside the Russian leader during the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380.

St. Sergius who founded the monastery was one of the most respected religious leaders in Russia during his time. He had over 4oo followers in Russia who would go on to found many other monasteries in northeastern Russia in the 14th century, including the Solovetsky, Kirillov and Simonov monasteries. St. Sergius was also an avid supporter of Dmitry Donskoi in his struggle with the Tatars, sending his monks to fight alongside the Russian leader during the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380.

The square in front of the monastery. The red brick building was a famous merchant house built in the 1902-1903. Initially it was rented by the church to local tradesmen. When the Bolsheviks took over following WWI, the local administration was placed in the building. In 1920 a portion of the building burned down and its outward appearance was altered significantly when it was reconstructed.

The square in front of the monastery. The red brick building was a famous merchant house built in the 1902-1903. Initially it was rented by the church to local tradesmen. When the Bolsheviks took over following WWI, the local administration was placed in the building. In 1920 a portion of the building burned down and its outward appearance was altered significantly when it was reconstructed.

The walls of the monastery. Throughout the centuries these walls helped protect the monastery from repeated attacks from invaders. In 1408 the monastery was devastated by a fire after a Tatar unit attacked it. The biggest threat to the monastery would appear two centuries later during during a 16-month Polish-Lithuanian siege from 1608-1610. A Polish army of 15,000 attacked the monastery in the winter of 1908. Despite significantly outnumbering the Russian army of around 2,000, the Russians managed to hold back the Polish army which retreated to the town of Dmitriev afterward.

The walls of the monastery. Throughout the centuries these walls helped protect the monastery from repeated attacks from invaders. In 1408 the monastery was devastated by a fire after a Tatar unit attacked it. The biggest threat to the monastery would appear two centuries later during during a 16-month Polish-Lithuanian siege from 1608-1610. A Polish army of 15,000 attacked the monastery in the winter of 1908. Despite significantly outnumbering the Russian army of around 2,000, the Russians managed to hold back the Polish army which retreated to the town of Dmitriev afterward.

The entrance to the monastery.

The entrance to the monastery.

Beautiful murals line the walls of the entrance.

Beautiful murals line the walls of the entrance.

Inside the monastery.

Inside the monastery.

The entrance from the back. The monastery gets hundreds of visitors every day from people all over Russia.

The entrance from the back. The monastery gets hundreds of visitors every day from people all over Russia.

The Predtechensky Church built on top of the entrance to the monastery between 1693-1699.

The Predtechensky Church built on top of the entrance to the monastery between 1693-1699.

The first stone cathedral in the monastery, the Troitsky Sobor. It was built in 1422 by Serbian monks who had fled to the monastery after the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The frescoes in the walls were painted by the greatest icon painters in Medieval Russia at the time, Andrei Rublev and Danil Chyorny. Muscovite Royalty was traditionally baptized in the church over the centuries.

The first stone cathedral in the monastery, the Troitsky Sobor. It was built in 1422 by Serbian monks who had fled to the monastery after the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The frescoes in the walls were painted by the greatest icon painters in Medieval Russia at the time, Andrei Rublev and Danil Chyorny. Muscovite Royalty was traditionally baptized in the church over the centuries.

People lining up to enter the church.

People lining up to enter the church.

The Sergiev Posad Bell Tower, built between 1741 and 1770. At 88 meters high, it is a fine example of Russian Baroque architecture and at one point had 50 different bells. In 1930 the Bolsheviks destroyed 25 of them, including the largest weighed over 64 tonnes. New bells were added to the tower in 2002-2004.

The Sergiev Posad Bell Tower, built between 1741 and 1770. At 88 meters high, it is a fine example of Russian Baroque architecture and at one point had 50 different bells. In 1930 the Bolsheviks destroyed 25 of them, including the largest weighed over 64 tonnes. New bells were added to the tower in 2002-2004.

The Uspensky Sobor built in 1585. The church’s layout and design is very similar to the Uspensky Sobor in Moscow’s Kremlin that goes by the same name. The Uspensky Sobor is the biggest church in the monastery. The smaller church in front of the Uspensky Sobor is called the ‘Chapel Over the Well’ church. It was built later in 1700.

The Uspensky Sobor built in 1585. The church’s layout and design is very similar to the Uspensky Sobor in Moscow’s Kremlin that goes by the same name. The Uspensky Sobor is the biggest church in the monastery. The smaller church in front of the Uspensky Sobor is called the ‘Chapel Over the Well’ church. It was built later in 1700.

The Uspensky Sobor and the Chapel Over the Well Church on the left and on the right is a church named after the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles, built in 1476.

The Uspensky Sobor and the Chapel Over the Well Church on the left and on the right is a church named after the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles, built in 1476.

People lining up to enter the Chapel Over The Well Church.

People lining up to enter the Chapel Over The Well Church.

More buildings in the monastery.

More buildings in the monastery.

Exiting the monastery.

Exiting the monastery.

Back outside near the walls.

Back outside near the walls.

The square in front of the monastery. In the early 20th century the area square was filled with traders and shopkeepers who sold their goods and services to locals. The Soviet Union closed down the shops in the latter half of the 20th century because it viewed them as engaging in ‘profiteering’ which was against the Soviet Union’s communist ideology.

The square in front of the monastery. In the early 20th century the area square was filled with traders and shopkeepers who sold their goods and services to locals. The Soviet Union closed down the shops in the latter half of the 20th century because it viewed them as engaging in ‘profiteering’ which was against the Soviet Union’s communist ideology.

Beside the monastery is a beautiful park with several historical buildings, including the Old Monastery Inn built in the neoclassical style in 1825 and partially rebuilt in the same style after a fire in 1838. After the 1917 revolution the building was nationalized and became the property of the state. In 2000 it was returned to the monastery and renovated in 2005-2007.

Beside the monastery is a beautiful park with several historical buildings, including the Old Monastery Inn built in the neoclassical style in 1825 and partially rebuilt in the same style after a fire in 1838. After the 1917 revolution the building was nationalized and became the property of the state. In 2000 it was returned to the monastery and renovated in 2005-2007.

Sergiev Posad also has its fair share of historical buildings. The main street in Sergiev Posad is Red Army Prospect which runs parallel to the monastery. These buildings were built in the 1880’s. At the start of the 20th century the yellow building on the corner hosted Sergiev Posad’s women’s gymnasium.

Sergiev Posad also has its fair share of historical buildings. The main street in Sergiev Posad is Red Army Prospect which runs parallel to the monastery. These buildings were built in the 1880’s. At the start of the 20th century the yellow building on the corner hosted Sergiev Posad’s women’s gymnasium.

Sergiev Posad’s Museum of History and Art.

Sergiev Posad’s Museum of History and Art.

The park outside the monastery.

The park outside the monastery.

The Y. Gagarin Palace of Culture, built in 1954 and an example of Soviet neoclassical architecture.

The Y. Gagarin Palace of Culture, built in 1954 and an example of Soviet neoclassical architecture.

Some old buildings on our way back to the train station.

Some old buildings on our way back to the train station.

Before catching the train we decided to stop by a local store to buy our favorite Russian beer ‘Mohnaty Shmel’, which translates into English as ‘furry bumblebee’. The beer is named after a famous Soviet song and it is by far the best Russian beer I have found so far. Highly recommend trying it.

Before catching the train we decided to stop by a local store to buy our favorite Russian beer ‘Mohnaty Shmel’, which translates into English as ‘furry bumblebee’. The beer is named after a famous Soviet song and it is by far the best Russian beer I have found so far. Highly recommend trying it.

Moscow Region Day Trips: Zvenigorod

Zvenigorod is a small Russian city located 45 kilometers west of Moscow on the Moskva River. According to the last census in 2010, the town had a population of just 16,395, which makes it astronomically tiny by Russian standards.

The city is best known for the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery located on top of a hill overlooking the Moskva River. The city also hosted the famous Russian short story writer and playwright Anton Chekhov after he graduated university in Moscow in the late 19th century. There are stories that Chekhov was such a rowdy character that he got in trouble with the local police who repeatedly fined him for the lavish, drunk parties he threw in the village.

The easiest way to get to Zvenigorod is to take an elektrichka from Moscow’s Belorusskaya Railway Station. The ticket costs 154 rubles, or around $3, and takes an hour and 25 minutes to get there.

Getting off at Zvenigorod station. It was a cold, cloudy and snowy day in early March when we visited.

Getting off at Zvenigorod station. It was a cold, cloudy and snowy day in early March when we visited.

Zvenigorod was first mentioned in historical records in the late 1300’s. The city’s main tourist attraction is the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, located about 1.5 kilometers from the city center. It was founded in 1398 by Savva Storozhevsky and is one of the few remaining artifacts of 14th century Muscovite Russia architecture.

Zvenigorod was first mentioned in historical records in the late 1300’s. The city’s main tourist attraction is the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, located about 1.5 kilometers from the city center. It was founded in 1398 by Savva Storozhevsky and is one of the few remaining artifacts of 14th century Muscovite Russia architecture.

Part of what makes the monastery so special is that it is essentially hidden in a forest, with trees surrounding the monastery from all sides. During the summer and fall when the trees are filled with leaves the monastery is barely visible.

Part of what makes the monastery so special is that it is essentially hidden in a forest, with trees surrounding the monastery from all sides. During the summer and fall when the trees are filled with leaves the monastery is barely visible.

There are also several estates and old homes sprinkled around the woods.

There are also several estates and old homes sprinkled around the woods.

Over the centuries the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery survived several episodes where it could have been completely destroyed. During the Polish invasion of Russia in the early 17th century the Poles captured the area on their way to Moscow. Two hundred years later the French would do the same under Napoleon in 1812.

Over the centuries the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery survived several episodes where it could have been completely destroyed. During the Polish invasion of Russia in the early 17th century the Poles captured the area on their way to Moscow. Two hundred years later the French would do the same under Napoleon in 1812.

The biggest threat to the monastery however came when the Bolsheviks took power in Russia following the Russian civil war in 1922. They declared an end to the old tsarist order and called for the destruction of private property and religion across Russia. As such, the regime’s biggest enemies became wealthy landowners, peasants and the church. In the 1930’s Stalin began demolishing churches across all of Russia. In 1936 there were plans to raze the monastery entirely and build a stadium in its place. Thankfully it was spared after prominent cultural figures lobbied for its rescue.

The biggest threat to the monastery however came when the Bolsheviks took power in Russia following the Russian civil war in 1922. They declared an end to the old tsarist order and called for the destruction of private property and religion across Russia. As such, the regime’s biggest enemies became wealthy landowners, peasants and the church. In the 1930’s Stalin began demolishing churches across all of Russia. In 1936 there were plans to raze the monastery entirely and build a stadium in its place. Thankfully it was spared after prominent cultural figures lobbied for its rescue.

Part of what makes the monastery so attractive is its location on top of a hill overlooking the Moskva River. The view is even prettier in the summer and fall when the river is visible.

Part of what makes the monastery so attractive is its location on top of a hill overlooking the Moskva River. The view is even prettier in the summer and fall when the river is visible.

Historically the monastery had a total of seven bell towers, but only six have survived.

Historically the monastery had a total of seven bell towers, but only six have survived.

A final threat to the monastery arose during the German invasion of the Soviet Union in WWII. The German army reached the outskirts of Moscow but never captured the city. Although Moscow was bombed by the Germans and hundreds of other cities to the west of Moscow were destroyed, Zvenigorod was skipped over. Many Russian cities that lie west of Moscow were significantly damaged during WWII, with some seeing more than 70% of their historic centers destroyed, such as Voronezh and Belgorod. Zvenigorod managed to escape this fate.

A final threat to the monastery arose during the German invasion of the Soviet Union in WWII. The German army reached the outskirts of Moscow but never captured the city. Although Moscow was bombed by the Germans and hundreds of other cities to the west of Moscow were destroyed, Zvenigorod was skipped over. Many Russian cities that lie west of Moscow were significantly damaged during WWII, with some seeing more than 70% of their historic centers destroyed, such as Voronezh and Belgorod. Zvenigorod managed to escape this fate.

The entrance to the monastery.

The entrance to the monastery.

The monastery gets a steady stream of tourists from Moscow and Russia year round. Even in the dead of winter there were tons of visitors.

The monastery gets a steady stream of tourists from Moscow and Russia year round. Even in the dead of winter there were tons of visitors.

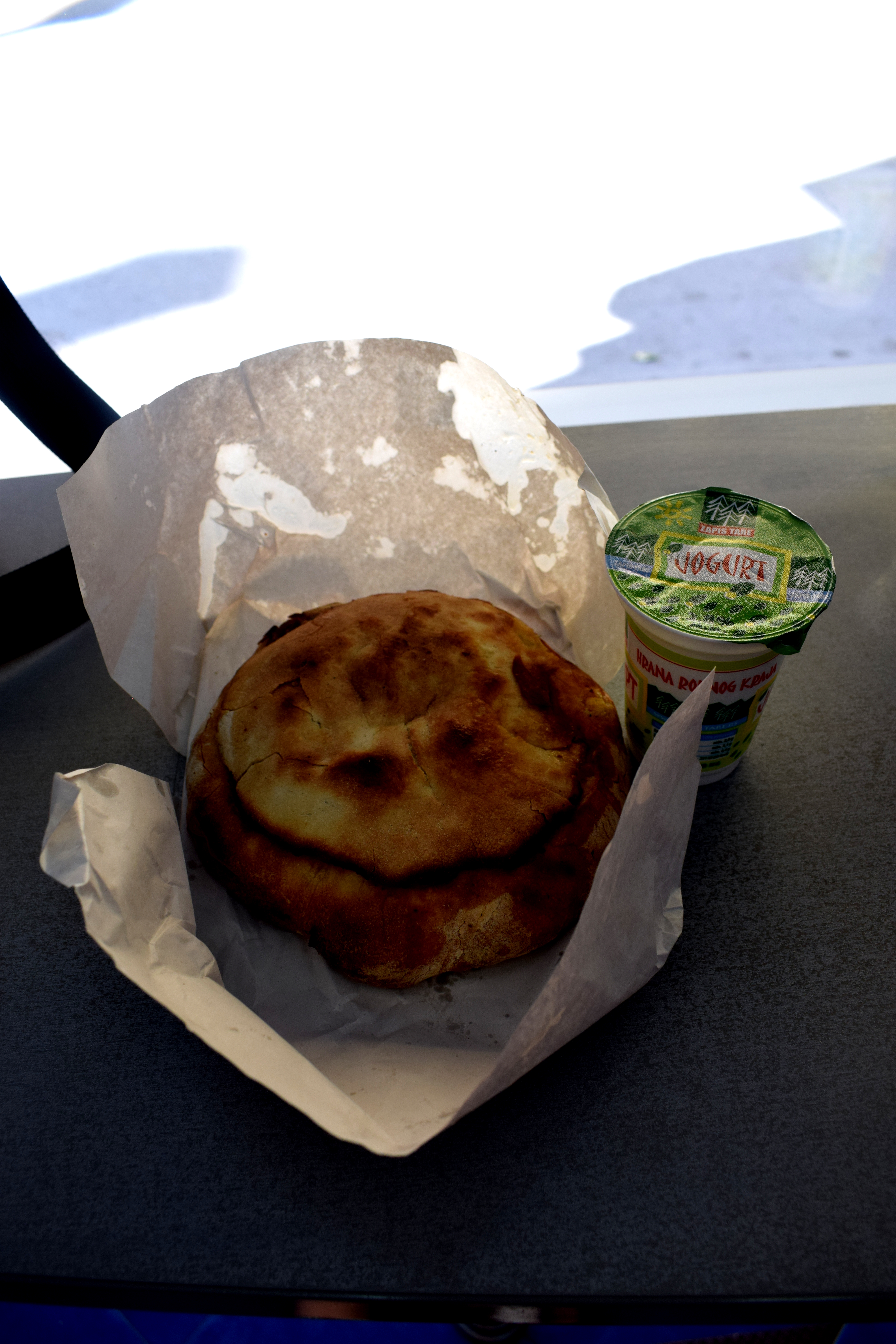

One reason people visit is because the monastery is known to make some of the best bread, pastries and cakes in the region. People often commute all the way from Moscow to buy the deserts baked by the monastery’s monks and to then sit and chat in the cafe above drinking tea.

One reason people visit is because the monastery is known to make some of the best bread, pastries and cakes in the region. People often commute all the way from Moscow to buy the deserts baked by the monastery’s monks and to then sit and chat in the cafe above drinking tea.

The interior of the cafe retains the same old wooden architecture that was there a hundred years ago.

The interior of the cafe retains the same old wooden architecture that was there a hundred years ago.

After leaving the cafe, visitors are free to roam around the walls of the monastery and take in the beautiful views.

After leaving the cafe, visitors are free to roam around the walls of the monastery and take in the beautiful views.

The central area of the monastery. When the Bolsheviks captured the monastery in 1918 they pillaged the frescoes and artifacts in the buildings, including the tomb of the monastery’s founder, St. Savva. It was shut down in 1919 and remained in an abysmal state for the remainder of the 20th century until the mid 1980’s when restoration efforts began.

The central area of the monastery. When the Bolsheviks captured the monastery in 1918 they pillaged the frescoes and artifacts in the buildings, including the tomb of the monastery’s founder, St. Savva. It was shut down in 1919 and remained in an abysmal state for the remainder of the 20th century until the mid 1980’s when restoration efforts began.

The Nativity of Mary Sobor, originally built in 1405. Further sections were added on in subsequent centuries.

The Nativity of Mary Sobor, originally built in 1405. Further sections were added on in subsequent centuries.

Zvenigorod began to decline in significance as a political and religious center following the 15th century. But in the mid 17th century the city experienced a revival in importance after the Russian Tsar Alexis decided set up his residence in the walls of the monastery.

Zvenigorod began to decline in significance as a political and religious center following the 15th century. But in the mid 17th century the city experienced a revival in importance after the Russian Tsar Alexis decided set up his residence in the walls of the monastery.

Tsar Alexis ruled Russia from 1645-1676. His reign oversaw wars with Poland and Sweden, the schism in the Russian Orthodox Church between Old Believers and church reforms initiated in 1653 to bring Russian Orthodox Church practices in line with Greek practices. He also ruled during a major Cossack revolt in southern Russia in 1670-1671. He spent most his time responding to these events in the walls of this monastery.

Tsar Alexis ruled Russia from 1645-1676. His reign oversaw wars with Poland and Sweden, the schism in the Russian Orthodox Church between Old Believers and church reforms initiated in 1653 to bring Russian Orthodox Church practices in line with Greek practices. He also ruled during a major Cossack revolt in southern Russia in 1670-1671. He spent most his time responding to these events in the walls of this monastery.

After Tsar Alexis died he was succeeded by his eldest son Feodor III who continued to use the monastery as his primary residence. Feodor III ruled Russia from 1676 to 1682 and assumed the throne when he was just 15 years old. He would rule Russia for only five years, dying in 1682 at the age of 20. After Feodor III’s death, the monastery declined in importance, especially when Peter the Great moved Russia’s capital to St. Petersburg in 1703.

After Tsar Alexis died he was succeeded by his eldest son Feodor III who continued to use the monastery as his primary residence. Feodor III ruled Russia from 1676 to 1682 and assumed the throne when he was just 15 years old. He would rule Russia for only five years, dying in 1682 at the age of 20. After Feodor III’s death, the monastery declined in importance, especially when Peter the Great moved Russia’s capital to St. Petersburg in 1703.

A group of three 17th century churches originally built to be the chamber for the Tsar Alexis’ wife. The clock tower in the upper left is the tallest building in the monastery.

A group of three 17th century churches originally built to be the chamber for the Tsar Alexis’ wife. The clock tower in the upper left is the tallest building in the monastery.

A beautiful doorway into the orthodox cathedral.

A beautiful doorway into the orthodox cathedral.

Back in the city center of Zvenigorod.

Back in the city center of Zvenigorod.

Overall, the monastery is a perfect day trip from Moscow and offers a unique chance to explore the ancient churches located within its walls and warm up inside with tea and deserts known to be some of the best in the region. While we did not have time to explore the town of Zvenigorod itself, there are also several things to see and do there, not the least of which is to visit Anton Chekhov’s old house where the famous Russian writer lived after graduating university in Moscow. Even though the best time to visit Zvenigorod is in the summer and fall, for those that can brave the elements, a visit in the winter is no less rewarding.

Overall, the monastery is a perfect day trip from Moscow and offers a unique chance to explore the ancient churches located within its walls and warm up inside with tea and deserts known to be some of the best in the region. While we did not have time to explore the town of Zvenigorod itself, there are also several things to see and do there, not the least of which is to visit Anton Chekhov’s old house where the famous Russian writer lived after graduating university in Moscow. Even though the best time to visit Zvenigorod is in the summer and fall, for those that can brave the elements, a visit in the winter is no less rewarding.

Moscow Region Day Trips: Kolomna

Kolomna is one of Russia’s oldest cities. Located 114 kilometers south of Moscow where the Moskva and Oka rivers meet, it is a typical example of a city in Russia’s provincial countryside, seeped with rich history and cultural wonders. Founded in 1177, it has a population of only 144,589 according to the latest census from 2010. But what the city lacks in size, it makes up for in history.

How to get there:

The best way to get to Kolomna is to take an “elektrichka”, the Russian word for suburban train. They leave every half hour from the Kazan Railway Station in Moscow. The ticket costs 250 rubles, or about $4.50 one-way, and the ride takes 2 hours and 20 minutes. Most elektrichkas are old and few have been updated since Soviet times. But they are fast and reliable and never late. Riding one is a blast from the past. Some things in Russia never change, and the electrichkas are one of them. You feel like you have traveled back in time to the Soviet Union with the Russian countryside whizzing past you.

There is nothing much to see at Kolomna’s train station when you arrive. But the historic core of the city is just a short tram ride away.

There is nothing much to see at Kolomna’s train station when you arrive. But the historic core of the city is just a short tram ride away.

Like their suburban rail counterparts, trams are the second thing in Russia that doesn’t ever seem to change. The trams in Kolomna were particularly old, but they rattled along sturdily toward the center. Each tram comes with a conductor who you buy your ticket from. A tram ticket costs 30 rubles, or around 50 cents.

Like their suburban rail counterparts, trams are the second thing in Russia that doesn’t ever seem to change. The trams in Kolomna were particularly old, but they rattled along sturdily toward the center. Each tram comes with a conductor who you buy your ticket from. A tram ticket costs 30 rubles, or around 50 cents.

When you see an enormous church towering high over the rest of Kolomna’s buildings, that is when you’ll know where to get off. Behold Archangel Michael’s Church, the tallest church in Kolomna, located outside the entrance to Kolomna’s Kremlin.

When you see an enormous church towering high over the rest of Kolomna’s buildings, that is when you’ll know where to get off. Behold Archangel Michael’s Church, the tallest church in Kolomna, located outside the entrance to Kolomna’s Kremlin.

Archangel Michael’s Church was built from 1820-1833 during the reign of Russian Czar Nicolas I (1825-1855). It has the hallmarks of traditional Russian imperial architecture. When the Bolsheviks came to power after WWI they closed the church down, emptied the interior of all its religious artifacts, and turned it into the city’s regional museum. It was renovated and reopened as a church in 2007.

Archangel Michael’s Church was built from 1820-1833 during the reign of Russian Czar Nicolas I (1825-1855). It has the hallmarks of traditional Russian imperial architecture. When the Bolsheviks came to power after WWI they closed the church down, emptied the interior of all its religious artifacts, and turned it into the city’s regional museum. It was renovated and reopened as a church in 2007.

The real beauty of Kolomna is the city’s medieval Kremlin. Kremlin is the Russian word for fortress and there are several cities across Russia that contain these architectural wonders. They were generally built alongside major rivers with their walls sheltering the city’s religious leaders and political elite from outside attackers. Kolomna’s Kremlin was built in 1525-1531 under the reign of Russian Czar Vasily III, who was Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505-1533. Kolomna’s Kremlin once had 17 towers and four gates to enter the city, but only seven have survived today.

The real beauty of Kolomna is the city’s medieval Kremlin. Kremlin is the Russian word for fortress and there are several cities across Russia that contain these architectural wonders. They were generally built alongside major rivers with their walls sheltering the city’s religious leaders and political elite from outside attackers. Kolomna’s Kremlin was built in 1525-1531 under the reign of Russian Czar Vasily III, who was Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505-1533. Kolomna’s Kremlin once had 17 towers and four gates to enter the city, but only seven have survived today.

The walls are around 18-21 meters high and form a half circle around the entrance to the historic core of the city. Kolomna was first mentioned in 1177 when the area was under the control of Kievian Rus’, the ancient first state of the East Slavs. It would suffer serious setbacks in the centuries to come, especially after the Mongols attacked Kievan Rus’ in 1240. It was not until 1380 that the town would rise up and rebel under the leadership of Moscow’s Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoi. Today Donskoi is a hero around the town and across all of Russia.

The walls are around 18-21 meters high and form a half circle around the entrance to the historic core of the city. Kolomna was first mentioned in 1177 when the area was under the control of Kievian Rus’, the ancient first state of the East Slavs. It would suffer serious setbacks in the centuries to come, especially after the Mongols attacked Kievan Rus’ in 1240. It was not until 1380 that the town would rise up and rebel under the leadership of Moscow’s Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoi. Today Donskoi is a hero around the town and across all of Russia.

The Statue to Dmitry Donskoi in front of Kolomna’s Kremlin.

The Statue to Dmitry Donskoi in front of Kolomna’s Kremlin.

Unfortunately much of the Kremlin was destroyed in subsequent centuries, but some old entrance gates have survived.

Unfortunately much of the Kremlin was destroyed in subsequent centuries, but some old entrance gates have survived.

Inside the Kremlin is a beautiful collection of medieval churches and old 19th century buildings. Pictured below is Cathedral Square, the Kremlin’s main square.

Inside the Kremlin is a beautiful collection of medieval churches and old 19th century buildings. Pictured below is Cathedral Square, the Kremlin’s main square.

The Uspensky Cathedral in the center of the square was originally built in 1379 before being reconstructed a few centuries later in 1672. In 1804 the frescoes within the cathedral were repainted. In 1929 the interior of the church was plundered by the Soviets and the cathedral was closed until 1989. Today it stands as a central symbol of the city.

The Uspensky Cathedral in the center of the square was originally built in 1379 before being reconstructed a few centuries later in 1672. In 1804 the frescoes within the cathedral were repainted. In 1929 the interior of the church was plundered by the Soviets and the cathedral was closed until 1989. Today it stands as a central symbol of the city.

This square served as the town’s central meeting point for centuries. Traders and merchants would come here to display their goods on Sundays after church service.

This square served as the town’s central meeting point for centuries. Traders and merchants would come here to display their goods on Sundays after church service.

To the right of the Cathedral is the Novo-Golutvin Monastery, built in 1799. A church-sponsored renovation program has significantly enhanced the town’s visual appeal by repainting and renovating the exteriors of these buildings.

To the right of the Cathedral is the Novo-Golutvin Monastery, built in 1799. A church-sponsored renovation program has significantly enhanced the town’s visual appeal by repainting and renovating the exteriors of these buildings.

Another view of Cathedral Square.

Another view of Cathedral Square.

One of the towers to the Novo-Golutvin Monastery.

One of the towers to the Novo-Golutvin Monastery.

During Soviet times these churches were completely neglected, left to crumble and disappear to the pages of history. Take a look at how Uspensky Cathedral looked in the late 1980’s.

During Soviet times these churches were completely neglected, left to crumble and disappear to the pages of history. Take a look at how Uspensky Cathedral looked in the late 1980’s.

And here’s that same church today. The improvements are amazing.

And here’s that same church today. The improvements are amazing.

There are several other churches dotted throughout the Kremlin, some built later during the 1600’s and 1700’s and later. One example is the Brusensky Monastery. Initially built in 1552 as a wooden structure, it was rebuilt in 1881-1883 in its current form. In 1922 the monastery was closed by the Soviets and its property confiscated with the monks forced to move out. A renovation of the church was finished in 2006.

There are several other churches dotted throughout the Kremlin, some built later during the 1600’s and 1700’s and later. One example is the Brusensky Monastery. Initially built in 1552 as a wooden structure, it was rebuilt in 1881-1883 in its current form. In 1922 the monastery was closed by the Soviets and its property confiscated with the monks forced to move out. A renovation of the church was finished in 2006.

The gates to enter the Brusensky Monastery.

The gates to enter the Brusensky Monastery.

Another church within the Brusensky Monastery, built in 1552 and renovated in 2006.

Another church within the Brusensky Monastery, built in 1552 and renovated in 2006.

Nikolai Gostiny Church. Built originally in 1501, and then again in 1751-1752. In the 1920’s Kolomna received an order from Moscow that the church had to be destroyed. The church used to be much bigger with a bell tower and courtyard. This is all that remains today.

Nikolai Gostiny Church. Built originally in 1501, and then again in 1751-1752. In the 1920’s Kolomna received an order from Moscow that the church had to be destroyed. The church used to be much bigger with a bell tower and courtyard. This is all that remains today.

Here’s how it looked in the early 1900’s before the Bolshevik revolution.

Here’s how it looked in the early 1900’s before the Bolshevik revolution.

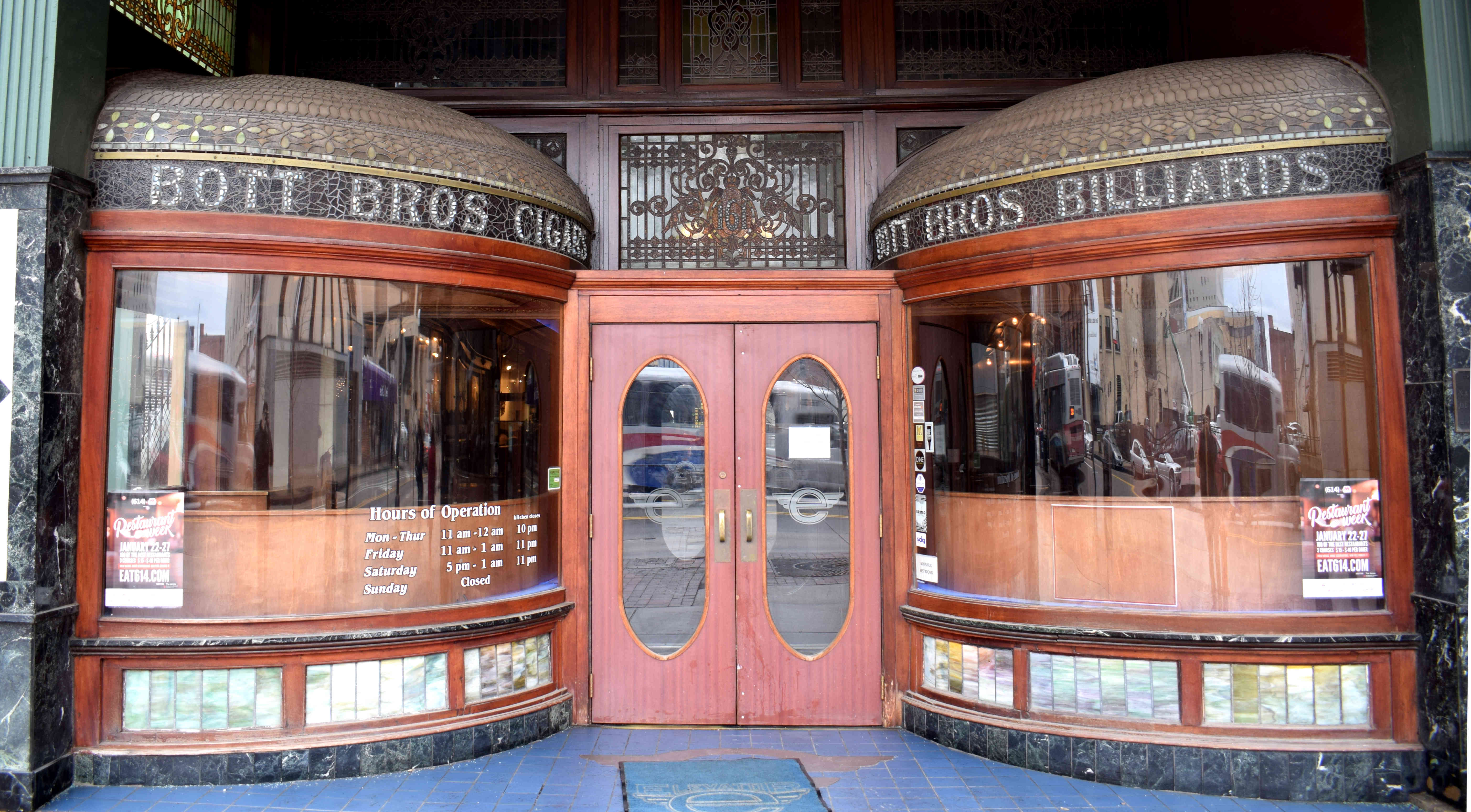

Of course, churches are not the only thing you can find within Kolomna’s Kremlin. You also have a beautiful pedestrian street called Lazhechnikova Street with several buildings from the 19th and early 20th century. Here you will find souvenir shops and outdoor cafes serving traditional Kolomna drinks and deserts.

Of course, churches are not the only thing you can find within Kolomna’s Kremlin. You also have a beautiful pedestrian street called Lazhechnikova Street with several buildings from the 19th and early 20th century. Here you will find souvenir shops and outdoor cafes serving traditional Kolomna drinks and deserts.

It was March and the weather in Russia was still cold so there weren’t many people. But in the summer these shops open up their cafes and people sit outside.

It was March and the weather in Russia was still cold so there weren’t many people. But in the summer these shops open up their cafes and people sit outside.

This building used to house the Kolomna City Duma before the revolution in the early 1900’s.

This building used to house the Kolomna City Duma before the revolution in the early 1900’s.

A small wooden room attached to the side of the brick housing looks like its about to fall off.

A small wooden room attached to the side of the brick housing looks like its about to fall off.

A souvenir shop to the side. Most of the buildings in the Kremlin are small one or two story buildings dating back to the 19th century.

A souvenir shop to the side. Most of the buildings in the Kremlin are small one or two story buildings dating back to the 19th century.

Kolomna cats.

Kolomna cats.

To the left on the door you see the words “Pastila” written. Pastila is a traditional Russian fruit candy made of different kinds of light airy paste. Kolomna is famous for producing its own brand sold across Russia.

To the left on the door you see the words “Pastila” written. Pastila is a traditional Russian fruit candy made of different kinds of light airy paste. Kolomna is famous for producing its own brand sold across Russia.

One of the best aspects of Kolomna are its wooden homes. Russians used to live in such homes in the early 20th century. As Russian cities expanded and modernized these homes were typically razed to the ground to make way for modern high rises. But in small Russian cities the wooden homes remain.

One of the best aspects of Kolomna are its wooden homes. Russians used to live in such homes in the early 20th century. As Russian cities expanded and modernized these homes were typically razed to the ground to make way for modern high rises. But in small Russian cities the wooden homes remain.

An old water pump. People used to use these to bring water back into their homes. A lot of villages in Russia still have them and some still work.

An old water pump. People used to use these to bring water back into their homes. A lot of villages in Russia still have them and some still work.

Wooden constructions were typical across Russia during the 19th and 20th century. It was a cheap form of building material compared with stone and brick and abundant across the country because of the vast woodland and forests.

Wooden constructions were typical across Russia during the 19th and 20th century. It was a cheap form of building material compared with stone and brick and abundant across the country because of the vast woodland and forests.

Another example of an old 19th century wooden home.

Another example of an old 19th century wooden home.

Each building is painted in a different color, adding to the liveliness of the place.

Each building is painted in a different color, adding to the liveliness of the place.

A window to one of these traditional homes.

A window to one of these traditional homes.

A local girl resting in the shade in Kolomna on a hot summer day in 1916.

A local girl resting in the shade in Kolomna on a hot summer day in 1916.

That same building in 2017.

That same building in 2017.

More Kolomna cats. In the background you can see the Moskva River.

More Kolomna cats. In the background you can see the Moskva River.

The Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. The stone structure was first built in 1764 and then later rebuilt in 1837.

The Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. The stone structure was first built in 1764 and then later rebuilt in 1837.

The Pyatnitskie Gates, the last surviving tower of the Kremlin where the gates are still intact.

The Pyatnitskie Gates, the last surviving tower of the Kremlin where the gates are still intact.

Lots of people were out and about despite the cold weather, enjoying the sun, walking with their children and pets.

Lots of people were out and about despite the cold weather, enjoying the sun, walking with their children and pets.

Old fresco paintings on the Pyatniskie Gates which have survived to this day. At one point, all of the towers looked like this.

Old fresco paintings on the Pyatniskie Gates which have survived to this day. At one point, all of the towers looked like this.

To the right there is a cute little shop you can order some”Kalachi”, the old Russian word for cake, or bread.

To the right there is a cute little shop you can order some”Kalachi”, the old Russian word for cake, or bread. Two Russian woman warming up with tea and biscuits. Despite the sunny weather and the start of spring, it’s still cold in March.

Two Russian woman warming up with tea and biscuits. Despite the sunny weather and the start of spring, it’s still cold in March.

Kalachi Na Vynos = Cakes To Go

Some of the architecture outside of the Kremlin. These are typical 19th century homes in Kolomna. The city looks eerily abandoned in places. Unfortunately, many young people leave Kolomna to live and work in Moscow which is only two hours away. As a result, the city is slowly emptying out and the population dying.

Some of the architecture outside of the Kremlin. These are typical 19th century homes in Kolomna. The city looks eerily abandoned in places. Unfortunately, many young people leave Kolomna to live and work in Moscow which is only two hours away. As a result, the city is slowly emptying out and the population dying.

A statue dedicated to man’s best friend.

A statue dedicated to man’s best friend. There have been many floods in Kolomna throughout history. Here you can see how high the water reached each year, with the highest being in 1970, closely followed by 1994 and 2013.

There have been many floods in Kolomna throughout history. Here you can see how high the water reached each year, with the highest being in 1970, closely followed by 1994 and 2013. Another beautiful old wooden Kolomna home overlooking the Moskva river.

Another beautiful old wooden Kolomna home overlooking the Moskva river. More Kolomna streets.

More Kolomna streets. Few of the buildings in Kolomna’s old town are higher than two stories.

Few of the buildings in Kolomna’s old town are higher than two stories.