I have a soft spot for Columbus. I grew up here in the outskirts of one of the city’s many suburbs.

It was the typical American suburbia childhood. A large house with a driveway and garage and lawn in a neighborhood filled with identical looking houses and garages and lawns.

Shopping centers, parking lots, drive thrus, fast food. And farms. Lots of farms.

Unfortunately living out in the suburbs, I didn’t interact much with downtown Columbus. We lived in our little suburban bubble and trips to the city were few and far between.

So it was a special joy to come back after so many years and explore the city I skipped out on growing up. What I found surprised me.

Columbus is in many ways a quintessential example of your stereotypical American city.

You could take its downtown and copy and paste it in virtually every other downtown in the Midwest and it would be hard to see any differences between them.

But actually if you dig a little deeper, Columbus does have its own features that make it unique.

We began our journey in one of these unique districts: German Village.

Located in the heart of downtown just across the Scioto River, German Village is a historic neighborhood settled by German immigrants in the early 19th century. The neighborhood retained its small-house, German style architecture all the way into the early 20th century.

Located in the heart of downtown just across the Scioto River, German Village is a historic neighborhood settled by German immigrants in the early 19th century. The neighborhood retained its small-house, German style architecture all the way into the early 20th century.

However, anti-German sentiment in WWI, along with plans to reconstruct American cities in the 1940s and 1950s by clearing slums, caused the destruction of one-third of the neighborhood. The village was slated for complete destruction following WWII, but activist citizens in the 1960’s managed to set up the German Village Commission and lobbied to save the neighborhood.

However, anti-German sentiment in WWI, along with plans to reconstruct American cities in the 1940s and 1950s by clearing slums, caused the destruction of one-third of the neighborhood. The village was slated for complete destruction following WWII, but activist citizens in the 1960’s managed to set up the German Village Commission and lobbied to save the neighborhood.

In 2007 it was chosen as a Preserve America Community by the White House. This put the area off limits to developers who would have loved to tear down the tiny historic houses and build larger homes in replacement.

Most of the houses in German Village are one or two stories high that retain their historic appearance to this day.

Most of the houses in German Village are one or two stories high that retain their historic appearance to this day.

Occasionally a larger home will pop up.

Occasionally a larger home will pop up.

Cobble-stoned streets abound.

Cobble-stoned streets abound.

The story of German Village shows just how much of a threat developers are to cities.

The story of German Village shows just how much of a threat developers are to cities.

Cities that fail to clearly define historic neighborhoods and set up zoning laws that ban the demolition of historic housing risk losing all the heritage that makes them unique. Had developers gotten their way in the 1960s, these German houses would not exist today. Instead this area would have been cleared for development, replaced department stores, highways and parking lots.

Thankfully Columbus managed to preserve some of the neighborhood. But it’s still a shame to think that many other parts of the city were razed to the ground in the 20th century and lost forever, such as Columbus’s central train station.

First built in 1851 and reconstructed several times afterward, it received its final form in 1897. Any city that values its history would fight to save every last brick of such a building.

You’d be forgiven for mistaking Columbus, Ohio, a mid-sized American city in the Midwest for any city in France or Germany or Spain. Everything about the building – the trams, the cobblestoned streets, the pedestrians – screams Europe.

So what happened to Columbus’s famed train station? Few people realize that most American cities prior to WWII looked very European. They had trams, they had trains, they had people cycling in their centers and lively neighborhoods with people walking and streetside cafes.

It was only after the United States adopted the federal highways program and embarked on massive construction of highways across the country from the 1950s to the 1980s that American cities lost their historic heritage. Local governments were encouraged to abandon rail travel in favor of highways, promoting car ownership and life in the suburbs.

Columbus was not spared this destruction. In 1976 the city demolished their train station. For over a decade it stood as a construction site until it 1993 it was replaced with the Greater Columbus Convention Center.

Now I’m no expert, but maybe, just maybe, the city could have held off on destroying one of its most beautiful buildings to construct this.

Now I’m no expert, but maybe, just maybe, the city could have held off on destroying one of its most beautiful buildings to construct this.

It’s not all bad news though. Walking around I was impressed with how clean the center was and the city’s laid-back feel.

Heading toward downtown from German Village takes you past Genoa Park, part of the larger Scioto Mile the city developed to connect Columbus to the Scioto River.

Heading toward downtown from German Village takes you past Genoa Park, part of the larger Scioto Mile the city developed to connect Columbus to the Scioto River.

Conceived in the early 2000s, the Scioto Mile is the city’s plan to reconnect Columbus with the Scioto River that runs through Columbus. Before construction began in 2008, the river was cut off from the city by a five-lane highway that followed its path.

Conceived in the early 2000s, the Scioto Mile is the city’s plan to reconnect Columbus with the Scioto River that runs through Columbus. Before construction began in 2008, the river was cut off from the city by a five-lane highway that followed its path.

Now that same five-lane highway is a public park. There are trees, jogging and cycling tracks, picnic tables, playgrounds and more. It was a rainy, January day when these photos were taken, but in the summer the park fills up with people.

Now that same five-lane highway is a public park. There are trees, jogging and cycling tracks, picnic tables, playgrounds and more. It was a rainy, January day when these photos were taken, but in the summer the park fills up with people.

The Scioto Mile is a successful example of a city reclaiming its urban space from cars and handing it back to pedestrians. Across the United States, cities have started to dismantle highways that were built in the 1970s that ran through their downtowns and replace them with public spaces. Columbus is following this trend.

The Scioto Mile is a successful example of a city reclaiming its urban space from cars and handing it back to pedestrians. Across the United States, cities have started to dismantle highways that were built in the 1970s that ran through their downtowns and replace them with public spaces. Columbus is following this trend.

Once you cross the river and delve deeper into downtown you reach what could possibly be Columbus’s most important monument, the LeVeque Tower.

At the time it was built in 1924 it was the fifth tallest building in the world and intentionally constructed to be six inches taller than the Washington Monument in DC. In 1975 the LeVeque Tower was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. The entire building was sold for just $4 million in 2011, with the purchasers announcing a complete restoration of the building for $26 million. Now it is a hotel.

At the time it was built in 1924 it was the fifth tallest building in the world and intentionally constructed to be six inches taller than the Washington Monument in DC. In 1975 the LeVeque Tower was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. The entire building was sold for just $4 million in 2011, with the purchasers announcing a complete restoration of the building for $26 million. Now it is a hotel.

Next to the LeveQue Tower is the entrance to Columbus City Hall.

And in front of City Hall is a statue to Christopher Columbus.

And in front of City Hall is a statue to Christopher Columbus.

The statue was transported by boat to Columbus, Ohio all the way from Genoa, Italy in 1955. Christopher Columbus grew up in Genoa before setting off from Spain on his voyage to cross the Atlantic in 1492 and discover America. This statue served as a gift from the city of his birth to the city of his name.

The statue was transported by boat to Columbus, Ohio all the way from Genoa, Italy in 1955. Christopher Columbus grew up in Genoa before setting off from Spain on his voyage to cross the Atlantic in 1492 and discover America. This statue served as a gift from the city of his birth to the city of his name.

It was an impressive statue when I visited in 2018, but unfortunately it’s gone now. In recent years protests have broken out in the United States over racial issues, culminating in the Black Lives Matter movement. When the protests hit Columbus, they demanded the statue be removed owing to his racist legacy toward Native Americans. There were even demands to rename Columbus to something else in order to erase any association with Christopher Columbus. In July 2020, the city caved in and took down the statue.

It was an impressive statue when I visited in 2018, but unfortunately it’s gone now. In recent years protests have broken out in the United States over racial issues, culminating in the Black Lives Matter movement. When the protests hit Columbus, they demanded the statue be removed owing to his racist legacy toward Native Americans. There were even demands to rename Columbus to something else in order to erase any association with Christopher Columbus. In July 2020, the city caved in and took down the statue.

While I do sympathize with the protestors regarding racial issues, I don’t think that historical monuments should be removed like this.

Walking further down Broad Street will eventually lead you to the Ohio Statehouse. As the capital of Ohio, Columbus hosts all of the state’s institutions.

Constructed in the Greek Revival Style in 1861, the Ohio Statehouse is arguably Columbus’s most beautiful building. The Ohio General Assembly and the Ohio Governor’s office are located in it. In front of the Statehouse is a statue to President William McKinley, the 25th president of the United States.

Constructed in the Greek Revival Style in 1861, the Ohio Statehouse is arguably Columbus’s most beautiful building. The Ohio General Assembly and the Ohio Governor’s office are located in it. In front of the Statehouse is a statue to President William McKinley, the 25th president of the United States.

Mckinley was from Ohio. He was the third American president to be assassinated in 1901, following Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and James A. Garfield in 1881. He was also the last American president to have participated in the American Civil War as a soldier.

Mckinley was from Ohio. He was the third American president to be assassinated in 1901, following Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and James A. Garfield in 1881. He was also the last American president to have participated in the American Civil War as a soldier.

This monument was erected to him in 1906, just five years after his assassination.

This monument was erected to him in 1906, just five years after his assassination.

There are two smaller statues to the left and right of the McKinley monument that are meant to represent peace and prosperity. On the left side, a woman attends to a girl, symbolizing peace.

While on the right side an older man looks down on a young boy, meant to symbolize prosperity.

While on the right side an older man looks down on a young boy, meant to symbolize prosperity.

Despite the rainy weather, it was impossible not to notice how clean Columbus was. Unlike New York or Philadelphia, I barely found any trash on the sides of the roads in the center. There was little graffiti on buildings or homeless people on the sidewalks.

Despite the rainy weather, it was impossible not to notice how clean Columbus was. Unlike New York or Philadelphia, I barely found any trash on the sides of the roads in the center. There was little graffiti on buildings or homeless people on the sidewalks.

Another thing I liked were the bike lanes in the center. In recent years, Columbus has expanded its bike lane network. While this pales in comparison to bike-friendly cities in Europe, it shows that even in the Midwest, in a car-dependent state like Ohio, people are beginning to realize that everything can be done by bike and there is no need for a car.

Another thing I liked were the bike lanes in the center. In recent years, Columbus has expanded its bike lane network. While this pales in comparison to bike-friendly cities in Europe, it shows that even in the Midwest, in a car-dependent state like Ohio, people are beginning to realize that everything can be done by bike and there is no need for a car.

Some colleagues in suits taking lunch.

Some colleagues in suits taking lunch.

Columbus has clearly been a victim of developers. There are little historic buildings left in the center showcasing the city’s old 19th and early 20th century architecture. While pockets of smaller two or three story buildings can still be found, most of it has been gobbled up by skyscrapers and modern high-rises. It was difficult to find any streets in the center that had enough uninterrupted historical buildings on them that could be converted into a pedestrian zone, the way Cumberland, Maryland has done. However, one short section of E Gay Street is a possible candidate for pedestrianization. Traffic was relatively slow on the street and most of the street is used for parking anyway. Moreover, the street had a lot of bars and restaurants on it. And because it is such a small section of the city, traffic would not take a major hit if it were pedestrianized and closed off to cars.

Columbus has clearly been a victim of developers. There are little historic buildings left in the center showcasing the city’s old 19th and early 20th century architecture. While pockets of smaller two or three story buildings can still be found, most of it has been gobbled up by skyscrapers and modern high-rises. It was difficult to find any streets in the center that had enough uninterrupted historical buildings on them that could be converted into a pedestrian zone, the way Cumberland, Maryland has done. However, one short section of E Gay Street is a possible candidate for pedestrianization. Traffic was relatively slow on the street and most of the street is used for parking anyway. Moreover, the street had a lot of bars and restaurants on it. And because it is such a small section of the city, traffic would not take a major hit if it were pedestrianized and closed off to cars.

A few more historic buildings downtown.

A few more historic buildings downtown.

While these buildings are nice, it is difficult to enjoy them to their full extent as they are overpowered by taller, modern structures made of steel and glass.

While these buildings are nice, it is difficult to enjoy them to their full extent as they are overpowered by taller, modern structures made of steel and glass.

In other cases, their facades are covered with advertising.

In other cases, their facades are covered with advertising.

One of Columbus’s most impressive buildings is the Atlas Building, built in 1905 and added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Buildings in 1977.

One of Columbus’s most impressive buildings is the Atlas Building, built in 1905 and added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Buildings in 1977.

The Atlas Building is a unique example of early 20th century American architecture, particularly because of how tall and narrow the building is.

The Atlas Building is a unique example of early 20th century American architecture, particularly because of how tall and narrow the building is.

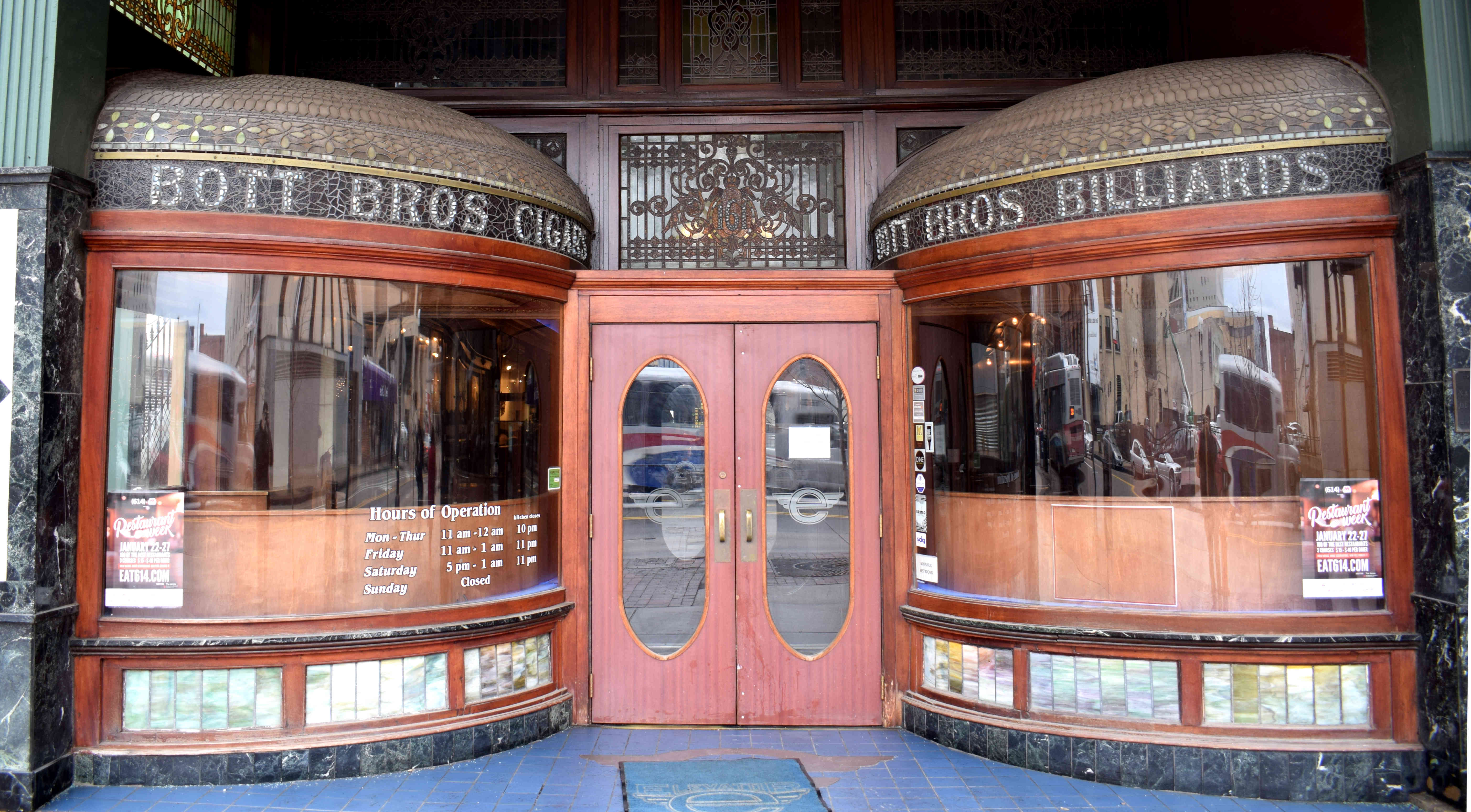

Overall the center of Columbus felt like a bit of mish mash of old buildings thrown together from different eras without any cohesive plan. Here we have a cool historic storefront sign.

Overall the center of Columbus felt like a bit of mish mash of old buildings thrown together from different eras without any cohesive plan. Here we have a cool historic storefront sign.

Old style restaurant facades in the center.

Old style restaurant facades in the center.

Food trucks in the city center. Columbus is known for its food scene. Some have boldly stated that Columbus has the best food scene in the United States.

Food trucks in the city center. Columbus is known for its food scene. Some have boldly stated that Columbus has the best food scene in the United States.

The business district with an interesting overpass.

The business district with an interesting overpass.

High Street is perhaps the most important street in Columbus. It passes by the Ohio State University Campus, the Columbus business and financial district, the popular Short North neighborhood and onward to Clintonville and suburbia.

High Street is perhaps the most important street in Columbus. It passes by the Ohio State University Campus, the Columbus business and financial district, the popular Short North neighborhood and onward to Clintonville and suburbia.

The Short North neighborhood in particular has become a hotbed of creativity and a hipster’s paradise. The area is dominated by gritty, industrial buildings with lots of small businesses and young people.

The Short North neighborhood in particular has become a hotbed of creativity and a hipster’s paradise. The area is dominated by gritty, industrial buildings with lots of small businesses and young people.

And while part of the reason the street is so attractive is the old gritty architecture, I saw many examples of buildings that had been ruined by developers. This is a perfect example for how to ruin a historic building by trying to mix the old and the new. Other examples abound.

And while part of the reason the street is so attractive is the old gritty architecture, I saw many examples of buildings that had been ruined by developers. This is a perfect example for how to ruin a historic building by trying to mix the old and the new. Other examples abound.

You can see historic Columbus contrasted with the modern Columbus in this photo.

You can see historic Columbus contrasted with the modern Columbus in this photo.

Further along the street you find the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral. Founded in 1910 and built in the Byzantine architectural style of the 6th century, it hosts a Greek Festival each year that is a major food event in Columbus.

Further along the street you find the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral. Founded in 1910 and built in the Byzantine architectural style of the 6th century, it hosts a Greek Festival each year that is a major food event in Columbus.

The entrance to the Short North neighborhood. Many young professionals and students are moving here owing to the proximity of the OXU campus nearby. But developers have caught on and are buying up old properties and replacing them with modern high-rises. It’s a question how much longer the neighborhood will retain its historic feel Just look at how the building on the right fails to blend in with the surrounding architecture.

The entrance to the Short North neighborhood. Many young professionals and students are moving here owing to the proximity of the OXU campus nearby. But developers have caught on and are buying up old properties and replacing them with modern high-rises. It’s a question how much longer the neighborhood will retain its historic feel Just look at how the building on the right fails to blend in with the surrounding architecture.

Some traditional storefronts on the street.

Some traditional storefronts on the street.

The sidewalk in front of the stores.

The sidewalk in front of the stores.

More construction.

More construction.

One final look down the street.

One final look down the street.

I’ll end up with a traditional American hole-in-the-wall dive bar. These places are great.

I’ll end up with a traditional American hole-in-the-wall dive bar. These places are great.

Columbus has the potential to be great. When I visited, it was raining. It was January. There were few people around in the center and this may have tainted my observations. I’ll have to return another time when the weather is nice and see Columbus in its full form.

Columbus has the potential to be great. When I visited, it was raining. It was January. There were few people around in the center and this may have tainted my observations. I’ll have to return another time when the weather is nice and see Columbus in its full form.

But despite the weather, I could see good things happening in the city. The conversion of highways along the Scioto River into a public park is one positive trend. The construction of bike lanes downtown to reduce car dependency is another. The story of German Village, a historic neighborhood off limits to developers is a third. These are examples of Columbus fighting to preserve its identity and ensure the city is liveable for future generations.

On the other hand, the amount of construction in historic areas I saw was worrying. Whenever a developer makes the case to tear down an old building today and replace it with an office complex, luxury apartments or a shopping mall, every native Columbusian should have a black-and-white picture of Columbus Union Station in their minds. A stunning, centuries-old building in the heart of downtown, lost forever.

Who’s to say that the buildings they are tearing down now and replacing with modern structures won’t be mourned in the same way? Let’s hope Columbus is able to save what’s left and keep the city a beautiful place to live for future generations.